In this article I’m going to unpick why developing a systems thinking approach into your design process is essential if you want solutions that work and are sustainable. It’s the second article, in a three-part series, where ExperienceLab share a selection of frameworks and strategies that we use to drive sustainable business value and reduce negative impacts on planet and people.

A little background

I am a big believer in human-centred design (HCD) and the positive value it can bring to organisations as they tinker with their services, develop strategies, or launch new products. As the name suggests the basis of these HCD activities are based on user research and uncovering the problems, issues and needs of customers or staff.

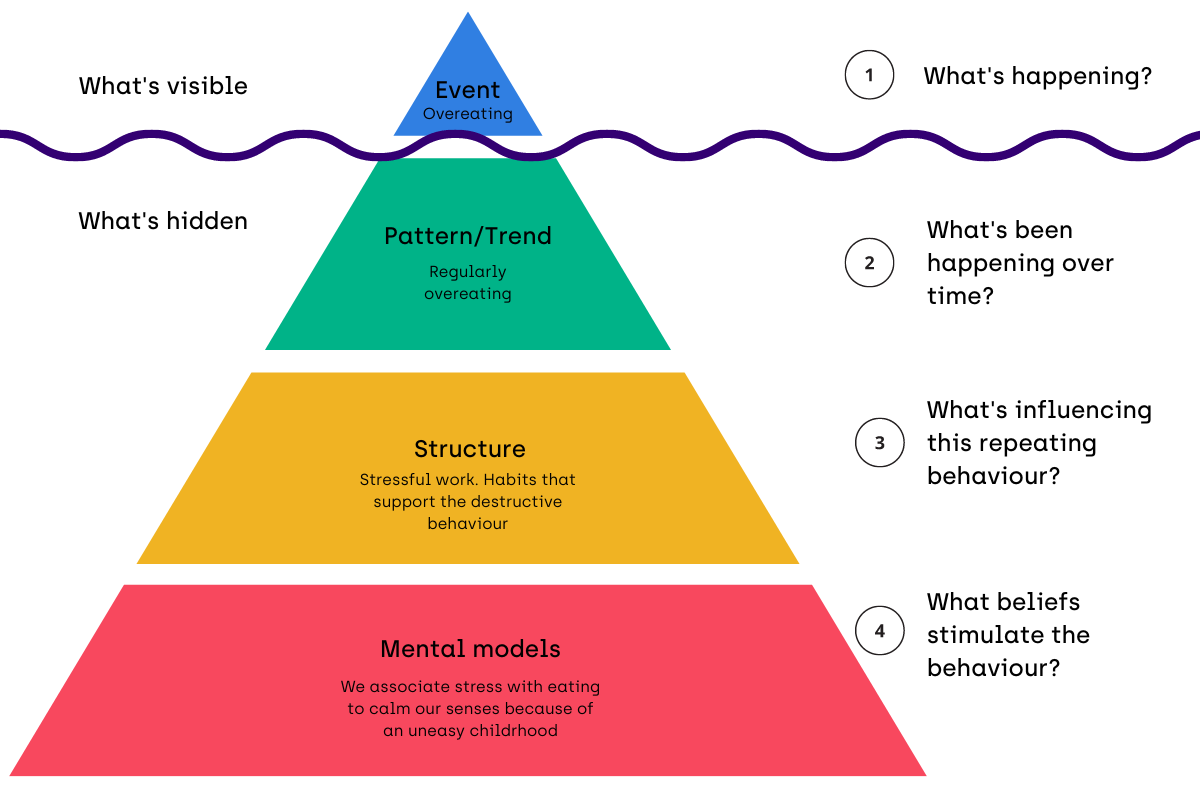

But simply taking this human-led mindset and looking for unmet needs can be problematic. At one level, these needs can often be better expressed as unmet wants and not necessarily a strong requirement or deep-rooted necessity. Furthermore, in my experience in public service design and research, these issues rarely standalone and often represent the tip of an iceberg with a series of interlocking patterns, structures and mindsets lurking beneath the surface.

Therefore, designing a solution to an issue(s) without considering the broader system is at best inconsequential and at worse exacerbating existing systemic issues.

Why systems thinking?

Systems thinking helps us to understand, intervene and make change in an increasingly complex world.

At ExperienceLab we support Serco to drive innovation and develop best practice supporting their mission to be a trusted partner of governments, delivering superb public services, that transform outcomes and make a positive difference for our fellow citizens.

But the problems of government are becoming ever more challenging. The in-tray of the latest government has some of the most stubborn and most wicked issues in living memory. Problems such as the cost-of-living crisis, climate change and the geographical inequality at the centre of the Levelling Up agenda are gigantic, difficult to define and have no single solution.

Wicked issues as defined by Horst Rittel in the 1960s are “a class of social system problems which are ill-formulated, where the information is confusing, where there are many clients and decision makers with conflicting values, and where the ramifications of the whole system are thoroughly confusing.”

But systems thinking and their related tools can help us to untangle and work within the complexity of these contemporary wicked problems.

Below are just two methods of the systems thinker.

- The Iceberg model – Adapted from The Iceberg Model by M. Goodman, 2002

- Continuous improvement

Understand the problem: The Iceberg Model

The iceberg model of systems thinking is one of the most approachable tools to understanding problem solving methods. The core concept of systems thinking is to help you see under the surface of structures, groups, organizations, and spot what are the root causes of problems or events.

The iceberg model helps you do just that. It provides an easy-to-follow four step framework that helps you to patiently deconstruct a problem(s) to uncover the root cause of an event or behaviour. Once this is done, you can make better responses as you are not simply reacting to the symptoms but responding to the root cause.

What are the four levels of the iceberg model?

The four levels of the iceberg model are the following: event, pattern, structure, and mental models. Each step digs a bit deeper and helps you shift your perspective so you can find the systems, the worldviews, that lead to the event in the first place.

Let’s see them one by one:

If we treat the symptom, we will never cure the disease. We need to understand what is causing the event to happen and apply fixes there.

Make change happen: continuous improvement

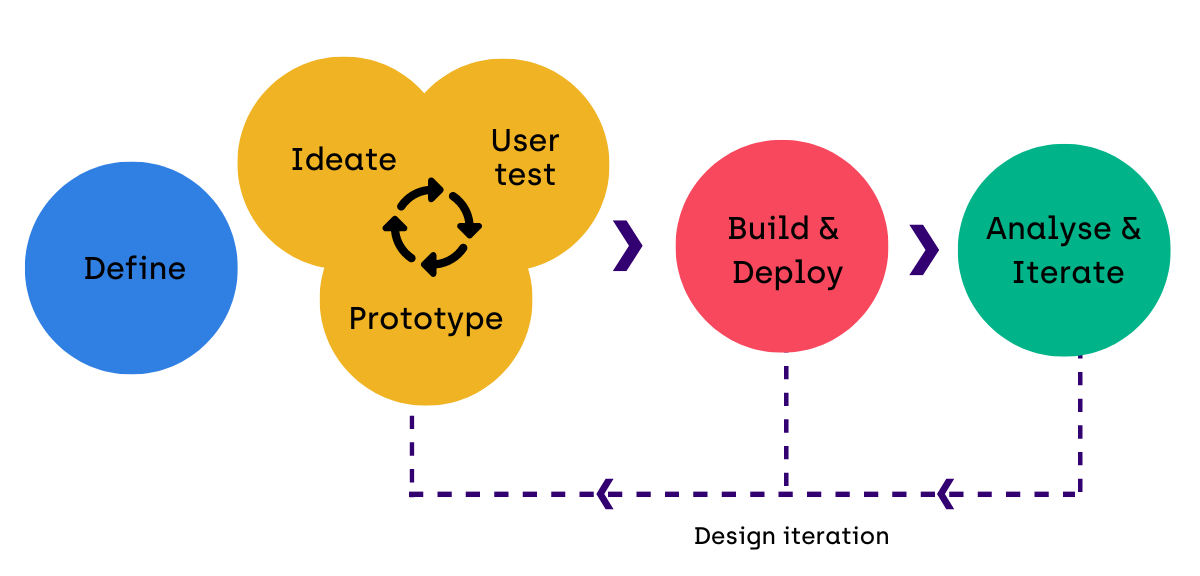

The most difficult part of systems thinking is making change actually happen; because at the heart of the systems thinking is the acceptance that the nature of wicked problems means the job of solving them is never done. The size and complexity of these problems means external conditions will continually change, new issues will arise, and our actions will have unintended consequences that require new responses.

As principle 8 in the Government Digital Service (GDS) framework states: Services are never ‘finished’.

Using agile methods means getting real people using your service as early as possible. Then making improvements throughout the lifetime of the service.

Therefore, this principle implies that there is no single design solution that makes a defined change. Rather, systemic change happens through a series of responses or connected interventions over time that can lead the systems to generate a more positive outcome.

Put simply, systems thinkers establish experiments and continual improvement processes within systems in an ongoing effort to improve products, services, or organisations. These efforts can seek tweaks (or incremental improvements over time) or breakthrough transformations all at once.

A typical continuous improvement process is the Understand, Build, Test, Evaluate, Iterate cycle. As outlined below.

This experimental approach is the basis of our design mindset at ExperienceLab. As we believe you cannot call yourself a designer until you have implemented something and made change happen.

In the next article we will look at our experimentation and change management approaches in more detail. And share the methods we use to make an important contribution to unravelling the knottiest of problems and deliver more sustainable design responses.

Further reading:

Sustainability in design: How to take a true sustainable mindset in your design process

The other U(s) in User Experience